Chief Complaint: 60-year-old Caucasian, diabetic female with subacute awareness of bilateral blurry central vision.

History of Present Illness: The patient had been on ethambutol as part of treatment for her recent diagnosis of Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (see Medical History below). Months after initiation of therapy, the patient noted increasing glare with bright lights in her left eye and arranged an appointment to visit an eye doctor. However, only days before the appointment she fell down a flight of stairs, resulting in a fracture of the C2/C3 vertebrae. She was hospitalized at another facility and placed in a stabilizing "halo" for 12 weeks. A few days into her hospitalization, the patient awakened from sedation and noticed blurry central vision in both eyes, which she described as "whited out". This was not addressed at the time and her medications were continued, including ethambutol. The blurry vision worsened over the next couple months. The patient saw an optometrist two months after the fall, who documented her vision to be 20/400 in each eye. The optometrist noted no disc edema referred the patient to a retinal specialist.

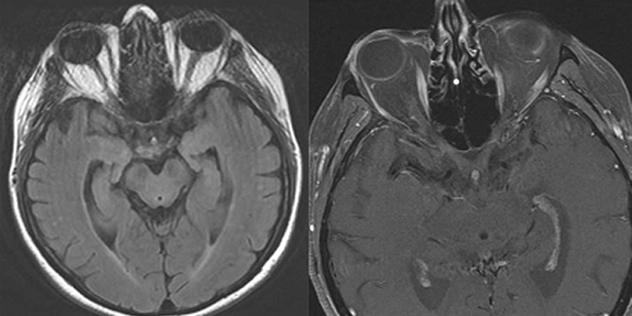

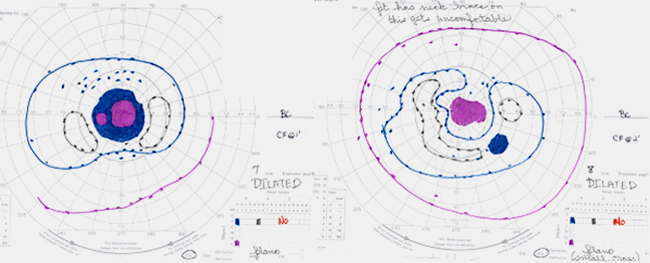

One month later the patient was examined by a local retinal specialist who noted that her vision had slowly worsened to CF at 2-3 feet in both eyes. The patient also reported dyschromatopsia with difficulty distinguishing brown from green and light blue from pink. The notes from that visit document a normal slit lamp examination, no affarent pupillary defect (RAPD), and intraocular pressures of 24 and 25 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. On ophthalmoscopy 2-3+ disc pallor was evident in both optic nerves, with spontaneous venous pulsations noted. An MRI of the brain and orbits was performed and showed no optic abnormality (see Figure 1). She returned to the retinal specialist who also performed a FDT 30-2 Threshold visual field test, which showed bilateral dense central scotomas (see Figure 2). The patient was then referred to the University of Iowa for further evaluation within two weeks.

Past Ocular History: Refractive error (corrected with trifocals). No ocular history of eye disease, surgery or trauma.

Medical History: The patient had a known history of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI) ten months prior to presentation. She was initially treated with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The rifampin was discontinued after the patient developed a rash during the first months of therapy. The ethambutol was started at 25 mg/kg/day for 2 months and then decreased to a maintenance dose of 15 mg/kg/day (800 mg daily). At the time she was seen at UIHC her ethambutol dose was 14.4 mg/kg/day (800 mg daily).

In addition, the patient had auto-immune Addison’s disease diagnosed 3 years ago, an 11-year history of diabetes mellitus, and a history of hypothyroidism. There were no other health issues. Recent PPD and HIV testing was negative.

Medications: Synthroid, Fludrocortisone, Hydrocortisone, Actonel, Lantus, Humalog, Ethambutol, Azithromycin, and PRN medications (Protonix, Tylenol, multivitamin, calcium)

Allergies: Codeine and sulfa medications. (Prednisone has caused erosive esophagitis as a side-effect in the past).

Family History: Diabetes Mellitus in mother and brother. Denies any history of glaucoma.

Social History: Denies smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol.

Review of Systems: Unremarkable. Specifically negative for renal or liver disease.

Ocular Examination:

|

|

|

|

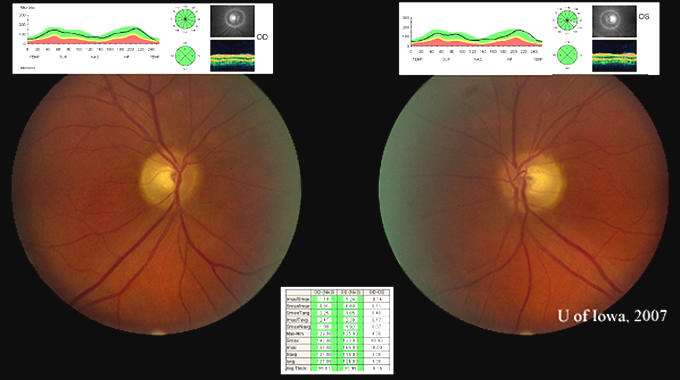

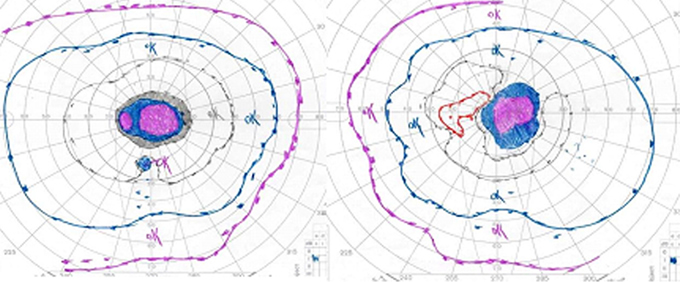

Course: In summary, this is a 60-year-old female with a history of mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI) treated with ethambutol for 2 months at 25 mg/kg/day and then 8 months at 15 mg/kg/day, now with subacute bilateral central vision loss, with associated bilateral temporal optic disc pallor. OCT was obtained to investigate possible visual recovery via the nerve fiber layer thickness. A normal thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer was seen in both eyes with no areas of focal thinning, average 95.83 OD and 95.99 OS (see Figure 4). The patient stopped the ethambutol immediately upon examination at the University of Iowa and her infectious disease physician was contacted about the toxic optic neuropathy. On follow-up with her infectious disease physician, the azithromycin treatment was continued and ciprofloxacin was added to the anti-MAI regimen. At her 3 week follow-up, the patient reported her vision slowly "lightening" with less dark shadows. She continues to have poor central vision, and difficulty distinguishing colors. On exam, color plate testing was poor, with 0/14 plates correct in each eye. Her visual acuity had improved to 20/400 OD and CF at 3 feet OS. Repeat Goldmann visual fields were performed at 3 and 6 weeks, showing some visual improvement of the dense central scotomas (see Figure 5).

|

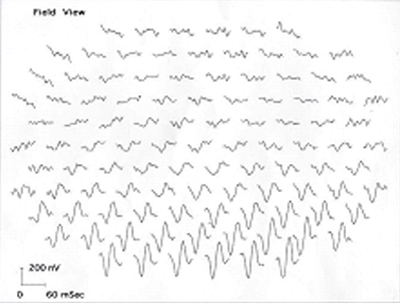

Course continued: The patient was evaluated in our Glaucoma Clinic for the high IOP measured previously. The patient used the latanoprost drops daily for 3 weeks and her pressure measured 28 in both eyes. Gonioscopy showed D35R, 1+ pigment in both eyes, and no synechiae. As no secondary causes of glaucoma were found, she likely has steroid induced ocular hypertension. It is believed the pressures were not contributing to her bilateral central visual field loss. Because of the optic neuropathy, a target IOP ≤ 20 was made by adding Timolol OD, Cosopt OS, and continuing the latanoprost OU. The patient returned for follow-up 3 weeks later. She had responded well to this medical therapy; her pressures were 16 in each eye. Also, a multi-focal electroretinogram (MERG) was obtained to ascertain whether there was a combination of retinal and optic nerve damage, as previously reported in cases of ethambutol-related optic neuropathies (Kardon et al., 2006). Her MERG showed a paracentral depression, especially superiorly in the first order waveforms of both eyes, thus demonstrating evidence of retinal involvement in addition to the optic neuropathy (see Figure 6).

|

Discussion: Toxic and metabolic optic neuropathies include the broad category of visual loss from medications, environmental toxins, and nutritional deficiencies. Recognition of these conditions is important because they are potentially reversible, particularly when caught early. Because the onset of these optic neuropathies is insidiously slow, most patients will already be symptomatic for weeks or months before being seen by a medical professional. Thus evaluation is recommended within 2 weeks of presentation, except for acute methanol toxicity, which is a medical and visual emergency (Levin et al., 2005).

There are numerous medications and toxins as well as nutritional deficiencies that can cause optic neuropathies, stressing the importance of taking a proper history and collecting an accurate medication list as well. Below is an abbreviated list of substances and vitamin deficiencies associated with optic neuropathy.

| TOXINS: | MEDICATIONS: | VITAMIN DEFICIENCIES: |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Depending on the patient’s presentation some ancillary tests may need to be performed. If suspicious for a nutritional optic neuropathy a CBC, serum B12, and RBC folate levels (provides a general index of nutritional status better than an isolated folate level) should be obtained, along with consideration for hematology consult if there is no underlying etiology for the vitamin deficiency. If concerned about alternate retinal cause of visual loss, a multifocal electroretinogram (MERG) and fluorescein angiogram may be appropriate to order. Lastly, an MRI may be necessary if the presentation is atypical (i.e. bitemporal visual field depression). The MRI should be ordered with contrast and orbital view with fat suppression to look for any demyelinating lesions and exclude compressive lesions (Levin et al., 2005).

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) encompasses two closely related organisms, M. avium and M. intracellulare. In patients with an intact immune system the major syndrome is pulmonary disease, whereas disseminated disease and cervical lymphadenitis is more commonly seen with advanced HIV infection. The clinical presentation of pulmonary MAC disease is quite non-specific and looks similar to other mycobacterial infections and COPD. Diagnosis is based on a complicated clinical case definition of chest scans, histopathologic specimen, positive sputum cultures, and positive bronchial wash cultures set forth by the American Thoracic Society. Successful treatment is based on multi-drug therapy similar to tuberculosis. The preferred regimens for pulmonary MAC is three drug therapy including a macrolide, either clarithromycin or azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Once the sputum cultures are negative most experts treat for at least another 12 months, with most patient with pulmonary MAC receiving a total of 18 to 24 months of therapy (Gordin et al., 2005).

Ethambutol is a bacteriostatic antimicrobial medication used as a first line defense against tuberculosis (TB) and MAC. Ethambutol’s therapeutic action is hypothesized to act as a chelating agent that disrupts a metal containing enzyme system in the mycobacteria. Inside the human mitochondria, the chelation of copper or zinc containing enzymes has been suggested as a optic neuropathy mechanism.

Since its beginning uses as a treatment for TB, ethambutol’s potential optic neuropathy toxicity was well recognized. Early animal studies showed that ethambutol caused lesions in the optic nerves and the optic chiasm, causing a diminished visual acuity in an often normal fundus exam (Miller et al., 2005).

The regimens of ethambutol doses vary by disease. The TB regimens can begin at either 50 mg/kg/day (maximum 4 grams) for 2 weeks or 25-30 mg/kg/day (maximum 2 grams) for 3 weeks, and then patients are maintained at 15-20 mg/kg/day (max 2 grams). For MAC regimens the maintenance dose is 15 mg/kg/day (maximum 2.5 grams). However depending on the species of mycobacteria a patient may be treated with a loading dose of 25 mg/kg/day for the first two months of therapy (Mandell et al., 2005; Micromedex 2007).

Ethambutol optic toxicity is known to be dose related. Leibold first described the dose dependent nature of ethambutol’s toxicity in the 1960s. He reported 18% of patients receiving high doses of ethambutol, > 35 mg/kg/day had vision loss, whereas only 3.3% of low dose therapy, < 30 mg/kg/day had vision loss (1966). Citron further characterized the ethambutol toxicities at 6% of patients receiving doses of 25 mg/kg/day and only 1% of patients on doses of 15 mg/kg/day had vision loss (1969). Because ethambutol is cleared mainly by the kidneys, doses need to be adjusted accordingly in any patient with renal insufficiency, based on their GFR (Micromedex 2007). If you recall, our patient did have a history of diabetes, however upon review of her chart she had no renal insufficiency based on normal creatinine values.

Once ethambutol toxicity is recognized and the medication is stopped many patients recover vision slowly over several months. Although medical literature suggests that the toxic effects of ethambutol are completely reversible with discontinuation, there have been numerous case reports of non-reversible vision loss after ethambutol use. Kumar described a series of 7 consecutive patients with severe vision loss caused by ethambutol at 25 mg/kg/day. After an average follow up of 8.3 months, only 3 of the 7 patients achieved visual recovery better than 20/200, with none of the patients having any predisposing risk factors to contribute to a poor prognosis (1993). Other investigators have also documented poor visual acuity recovery despite discontinuation of ethambutol at the onset of visual symptoms (Melamud et al., 2003).

When starting ethambutol, every patient should be warned about the potential visual toxicity. If patients have any symptoms of decreased acuity, reduced color discrimination, or visual field loss, the medication should be discontinued immediately and the prescribing physician notified. There are differing recommendations for monitoring the ethambutol related optic toxicity. The manufacturer recommends patients receiving ethambutol should have visual acuity testing before initiation of therapy and then periodically. Also the manufacturer recommends monthly eye examinations in patients receiving doses of 25 mg/kg/day or greater (Micromedex 2007). Recommendations for the routine visual acuity assessment prior to starting ethambutol have also been made by the Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the American and British Thoracic Societies (Thorax 1998; Bass et al., 1994). However, the committee no longer recommends visual acuity assessment during routine follow-up. Assessment of red-green color vision prior to treatment is also recommended by the American Thoracic Society. The TB and Chest Service of the Department of Health of Hong Kong also published guidelines recommending baseline vision tests for both visual acuity (Snellen chart) and red-green color vision (Ishihara chart), however these tests do not require an ophthalmologist’s expertise (Hong Kong Annual Report 2002).

In summary, we present a classic case of ethambutol related toxic optic neuropathy. Our patient presented with painless, progressive, bilateral central vision loss and blue-yellow dyschromatopsia. The patient’s visual acuity was count fingers at 2 feet in both eyes and her visual fields demonstrated bilateral central scotomas. Ophthalmoscopy demonstrated a mild temporal pallor of both optic discs, however her OCT was promising with a normal average nerve fiber thickness seen in both eyes. Upon presentation she was taking 14.4 mg/kg/day of ethambutol. According to previous reports only 1% of patients on this dose would experience toxic optic neuropathy. She appropriately discontinued the ethambutol and continued monitoring of her visual acuity recovery and her MAC infection. This case is being presented to remind practitioners of the importance of knowing a patient’s past medical history and medication list when evaluating vision loss. Lastly, the importance of proper counseling of the visual side effects when starting a medication like ethambutol is imperative. The need to discontinue the medication immediately at the onset of any visual disturbances and follow-up with the treating physician should be reinforced with every patient taking these antibiotics.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

Grace EM, Lee AG: Ocular Sardoidosis: Ethambutol Toxicity and Optic Neuropathy: 60-year-old female with bilateral painless central vision loss. EyeRounds.org. November 5, 2007; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/75-Ethambutol-Toxicity-Optic-Neuropathy.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.