Chief Complaint: Double vision.

History of Present Illness: A 46-year-old female patient presented to the Oculoplastics Clinic reporting double vision and visual distortion. The patient first noticed binocular horizontal diplopia two months prior to her visit. She described diplopia in primary position that worsened in right gaze and she had resorted to wearing an occlusive patch in order to control her symptoms. Three months prior to the current visit the patient noted the presence of a large blood vessel above her right eye. She also reported a whooshing sound in her right ear for 2-3 months.

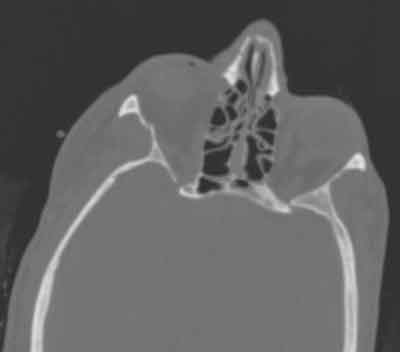

Past Ocular History: The patient was in a bicycle accident four months prior during which she sustained a small zygomaticomalar complex fracture (Figure 1). The patient was seen in the ophthalmology clinic three weeks later and was noted to have no diplopia, no gaze restriction, and a normal eye exam. She was asked to follow up two months later.

Medical History: Alcohol dependency and depression

Medications: Claritin® (loratadine)

Family History: Substance abuse, neck cancer, heart disease.

Social History: Alcohol dependency

|

|

|

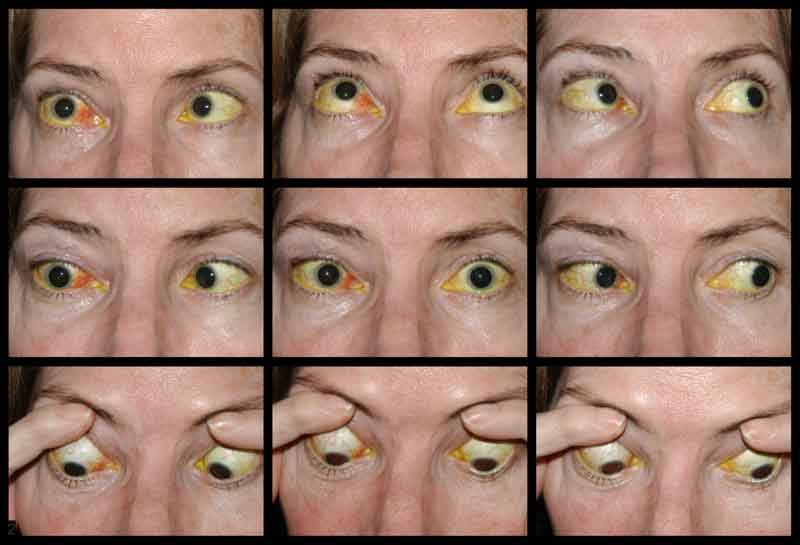

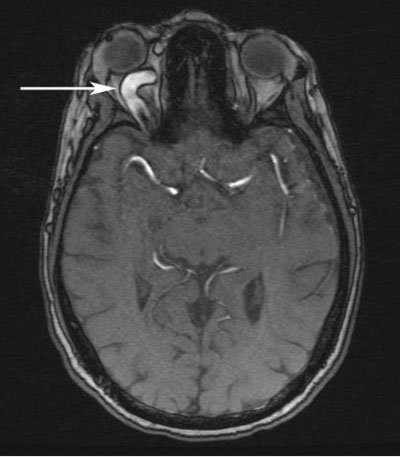

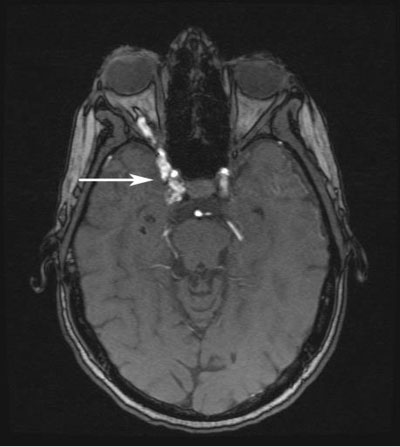

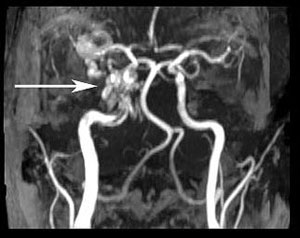

Course: A presumptive diagnosis of right-sided carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) was made based on clinical suspicion and the findings of proptosis, venous engorgement, orbital bruit, and abduction deficit. The patient was sent for MRI/MRA imaging of the brain that afternoon. The images demonstrated a right CCF as well as a markedly dilated right superior ophthalmic vein (Figures 4, 5, and 6). The patient was then seen in the Neurointerventional Clinic and scheduled for coiling of the fistula later that week.

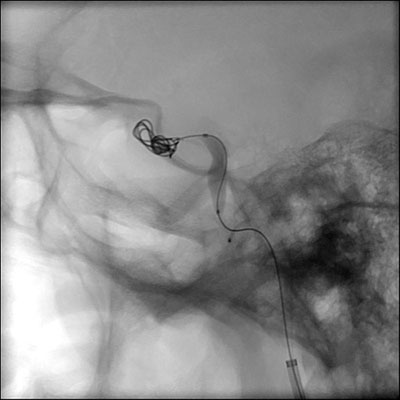

The patient underwent coiling of the right internal carotid artery (Figures 7 and 8). During the procedure, a high flow, expansive connection between the artery and the cavernous sinus and collateral veins was noted. There was also extensive arterial damage to the right cavernous internal carotid artery consistent with dissection. Good flow was seen to cross a patent anterior communicating artery so the fistula was treated with right internal carotid artery sacrifice, using coil embolization. Fortunately, the right ophthalmic artery remained perfused via collateral circulation. After the procedure the patient had an unremarkable hospital course and she was discharged home six days later.

|

|

| Figure 4: Magnetic Resonance Angiogram (MRA) image demonstrating an enlarged superior ophthalmic vein (arrow). | Figure 5: MRA demonstrating a right carotid cavernous fistula (arrow) |

|

|

|

| Figure 7: Intraoperative image demonstrating coil being deployed within the internal carotid system | Figure 8: Postoperative image showing coils within the internal carotid artery |

A carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF) is an abnormal communication between the venous cavernous sinus and the carotid artery. The fistula may occur spontaneously but usually occurs following some sort of head trauma, as jn the case of our patient. In one retrospective study, the time to presentation following injury ranged from one day to as late as 2 years.

There are four distinct types of fistulas (types A-D). A type A fistula is a direct, high flow fistula between the cavernous internal carotid artery and the cavernous sinus. It is the most common CCF following head trauma. Direct fistulas are thought to form from a traumatic tear in the wall of the cavernous internal carotid artery or following rupture of an aneurysm. Thus high pressure arterial blood gains rapid access to the venous system and leads to venous hypertension.

Type B-D, or indirect fistulas, occur between meningeal branches of the external or internal carotid artery and the cavernous sinus. These are low-flow fistulas. The etiology of types B-D is unclear, but they have been associated with pregnancy, sinusitis, age, and trauma. Symptoms are usually mild and may include dilated conjunctival and episcleral vessels and mild proptosis. These low flow fistulas generally resolve without treatment.

The onset of symptoms with a Type A fistula is usually rapid and can be very dramatic. Patients with a direct Type A fistula generally present with varied complaints, including unilateral visual loss, proptosis, lid swelling, pulsatile tinnitus and/or diplopia. A triad of clinical findings has been described as exophthalmos, orbital bruit, and dilated conjunctival vessels. Clinical findings include venous congestion of the eyelids, conjunctiva and episcleral vessels, cranial nerve palsies (3, 4, or 6), visual loss, proptosis, elevated intraocular pressure, optic disc edema, and dilated and tortuous retinal vessels.

In one retrospective study of 11 traumatic CC fistulas the most common clinical signs were proptosis, dilated conjunctival vessels, and an orbital bruit, all of which were found in 100% of the patients (Brosnahan, 1992). The second most common clinical finding was conjunctival chemosis, occurring in 10/11 patients. 8/11 patients has a sixth nerve palsy while 5/11 patients had a third nerve palsy and 5/11 had a fourth nerve palsy. An efferent pupillary defect secondary to a third nerve palsy was present in 5/11 patients. Less common findings included elevated intraocular pressure (range 26-30 mmHg.3/11 patients), loss of vision(2/11 patients), optic disc edema (2/11 patients), and dilated retinal vessels (4/11 patients).

Once a direct CCF is identified it is important to direct the patient to the appropriate treating specialist, either an interventional neurologist or neurosurgeon. Direct fistulas always require treatment. The literature is replete with different treatment modalities, including transarterial or transvenous embolization with coils, liquid embolic agents, balloon embolization, and stent placement. The success rate of closing the fistula with these treatments ranges from 55-99%. Potential complications of treatment include worsening of an oculomotor nerve palsy and loss of vision.

Diagnosis: Carotid Cavernous Fistula

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

>Cohen AW, Allen R. Carotid Cavernous Fistula. EyeRounds.org. May 14, 2010; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/111-Carotid-Cavernous-Fistula.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.