INITIAL PRESENTATION

Chief Complaint: Diplopia, left decreased vision, and left forehead numbness worsening over 3 months

History of Present Illness

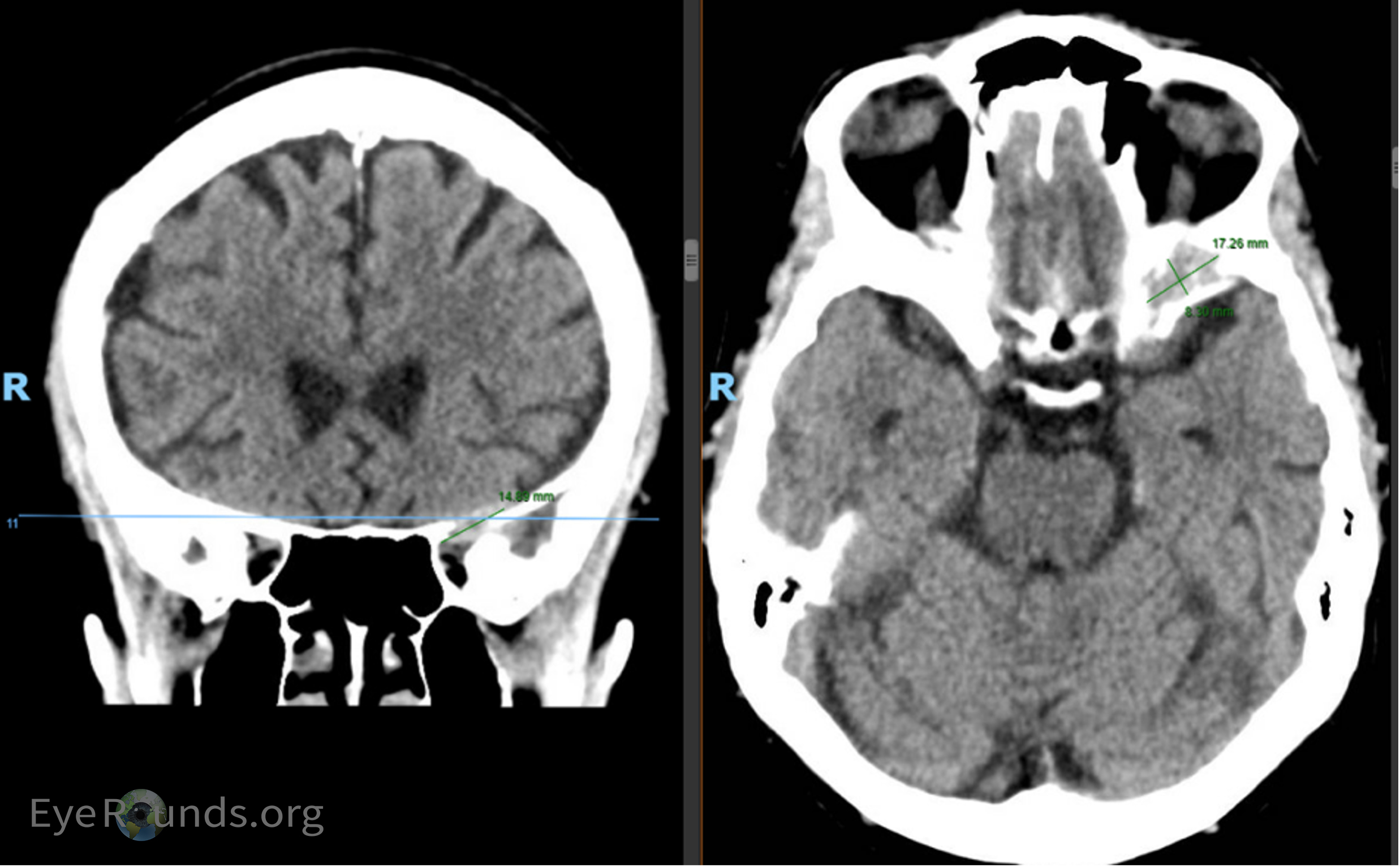

A 75-year-old female with a history of breast cancer (diagnosed 1996) in remission presented to an outside Emergency Department (ED) for evaluation of decreased vision of the left eye and numbness of the left forehead (Figure 1). CT imaging at the outside institution was reported as negative for intracranial or orbital pathology (Figure 2a). Over the course of 3 months, she developed further vision loss of her left eye, progressive binocular diplopia, and left eyelid drooping. She presented to our ED where MRI imaging revealed interval development of an enhancing lesion involving the left superior orbit and cavernous sinus (Figure 2b). The patient was seen in the neuro-ophthalmology clinic for evaluation.

Past Ocular History

Past Medical History

Past Surgical History

Medications

Allergies

Family History

Social History

Review of Systems

OCULAR EXAMINATION

| OD | OS | |

|---|---|---|

| Lids/lashes | Normal | Normal |

| Conjunctiva/sclera | Clear and quiet | Clear and quiet |

| Cornea | Diffuse punctate epithelial defects | Diffuse punctate epithelial defects |

| Anterior chamber | Deep and quiet | Deep and quiet |

| Iris | Normal architecture | Normal architecture |

| Lens | 1+ nuclear sclerosis | 1+ nuclear sclerosis |

| Anterior vitreous | Normal | Normal |

| OD | OS | |

|---|---|---|

| Disc | Normal | Normal |

| Cup-to-disc (C/D) ratio | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Macula | Normal | Normal |

| Vessels | Normal | Normal |

| Periphery | Normal | Normal |

DIAGNOSIS: Metastatic thyroid carcinoma of the orbit

CLINICAL COURSE

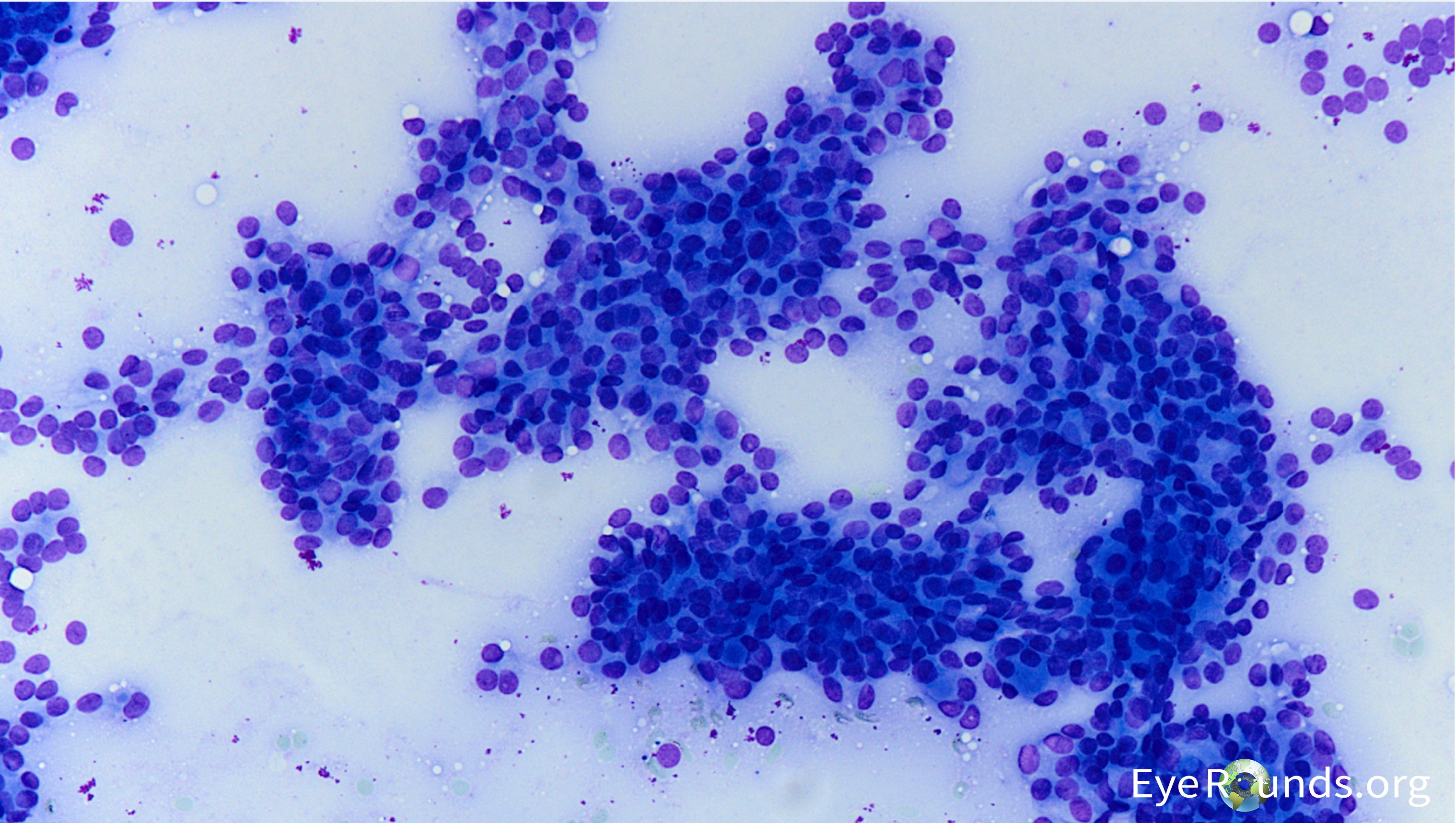

The patient’s presentation, history, and imaging studies were most concerning for metastatic disease involving the left cavernous sinus, left sphenoid wing, and left orbital apex causing multiple cranial neuropathies (CN2, 3, 4, and V1). A PET/CT of the total body showed avidity of the left sphenoid wing in the area of the orbital lesion, suggestive of neoplasm. There was no increased avidity elsewhere. The patient subsequently underwent orbital biopsy which showed yielded a tan-brown soft friable tissue sample. Intraoperative cultures for aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal elements were negative for growth, and flow cytometry was negative for non-Hodgkins type lymphoma. Histopathology was consistent with thyroid carcinoma (see Figure 6). She underwent fine needle aspiration of her thyroid (Figure 7a and 7b), and cytopathology findings were consistent with a low-grade thyroid tumor and compatible with papillary or follicular carcinoma. Histopathology demonstrated an adenocarcinoma, with an immunophenotype consistent with thyroid carcinoma (CK7 positive, CK20 negative; thyroglobulin, TTF-1 and PAX8 positive – See Table 1). She underwent palliative left orbital radiation for her orbital metastasis and subsequently passed away from complications of cardiogenic shock.

| Staining | Result |

|---|---|

| Pankeratin | Positive |

| Cytokeratin 7 | Positive |

| Thyroglobulin | Positive |

| TTF-1 | Positive |

| PAX8 | Positive |

| CK20 | Negative |

| ER | Negative |

| PR | Negative |

| GCDFP15 | Negative |

| GATA-3 | Negative |

| CDX-2 | Negative |

| Napsin A | Negative |

| WT-1 | Negative |

| SATB2 | Negative |

| CEA | Negative |

| Calretinin | Negative |

| AR | Negative |

DISCUSSION

Etiology/Epidemiology

Thyroid carcinoma is a rare primary source of orbital metastasis and it is also very rare for orbital metastases to be the initial presentation for thyroid carcinoma. Our patient had no known history of goiter or thyroid abnormalities, and thus her orbital lesion as the first presentation of metastatic thyroid carcinoma was a surprising diagnosis.

The most common metastases to the orbit were previously considered to result from breast, prostate, lung, and skin cancers, in that order. (1) A more recent review of the literature by Palmisciano et al. demonstrated that the most frequent primary sources of orbital metastases were breast (36.3%), melanoma (10.1%), prostate (8.5%), carcinoid (6.6%), and lung cancers (5.6%). Thyroid cancer represented one of the rarest sources at 1.5% of cases in the review. (2)

A 2013 PubMed search analyzing articles and case reports from 1979 to 2012 of documented thyroid metastases to the choroid or orbit revealed only 31 reported cases. Of these, papillary thyroid carcinoma was most common (35%) followed by follicular thyroid carcinoma (26%) and then medullary thyroid carcinoma (19%). (3) In 7 out of 9 cases with thyroid metastasis to the orbit, orbital symptoms were the first presentation of the underlying malignancy. (3)

A similar case was previously reported by Pagsisihan et al., where a 49-year-old woman with no previous thyroid disease presented with 2 years of diplopia and right eye blurry vision, ptosis, and orbital tenderness, with a lytic orbital lesion found to be papillary thyroid carcinoma. That patient was found to have metastases throughout her body and underwent RAI therapy. (4) Mahyuddin et al. reported three cases of female patients aged 28-65 years old with orbital metastases as the initial presentation of thyroid carcinoma. (5) Upon thorough workup, an asymptomatic thyroid mass was discovered in all patients and the diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis was made.

In addition to orbital metastases from an existing cancer, primary malignant and benign tumors are also in the differential for orbital masses. A recent retrospective case series by Demirci et al. on orbital tumors in the senior adult population found that the most common orbital masses were malignant lymphoma (24%), idiopathic orbital inflammation (10%), and cavernous hemangioma (8%). (6) In contrast, in children, the most common orbital masses are cystic lesions, vascular lesions (capillary hemangiomas), optic nerve/meningeal tumors, and rhambdomyosarcoma. (6, 7) Further benign etiologies of optic masses include optic nerve sheath meningioma, schwannoma, and neurofibroma. (8)

Signs/Symptoms

Presenting signs and symptoms of orbital metastases include diplopia, extraocular motility deficits, globe displacement, proptosis, enophthalmos, and pain. Decreased vision and RAPD may also occur if there is optic nerve involvement. (6) In the case where thyroid metastasis is suspected, other signs and symptoms like a goiter, thyroid nodule, hoarseness, or trouble swallowing may also be present.

Diagnostic tests/Work-up

Diagnostic tests should be aimed at evaluating deficits, establishing a baseline, and localization of the causative lesion if possible.

In thyroid cancer, thyroid function tests (TSH, T3 and T4) are typically normal and do not correlate with neoplastic activity. (9) Thyroid cancer does not commonly impact secretion of these hormones. However, a history of thyroid cancer treatments such as radioactive iodine or thyroid removal may have an impact on these laboratory values. Regular monitoring of thyroid function is important for patients with thyroid cancer, especially after thyroid surgery or radioactive iodine therapy, to ensure appropriate management of thyroid hormone levels. (9)

When establishing the presence of an orbital mass, imaging with CT or MRI can be done to visualize the mass and surrounding structures for aid in diagnosis and surgical planning if needed. MRI is the preferred imaging modality due to its delivery of higher-resolution images, but CT offers lower costs and quicker image acquisition.

If the thyroid is suspected as the primary site of a metastatic lesion, further diagnostic tests such as thyroid ultrasound, radioactive iodine uptake scan, or fine-needle aspiration biopsy may be performed to assess and characterize the extent of the cancer and determine a specific type.

PET-CT or bone scans can be done to evaluate metastatic burden of disease. Biopsy of the lesion is required for definitive diagnosis.

Treatment/Management

Treatment modalities for orbital metastases include tumor resection, orbital exenteration, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiation. There is poor prognosis for patients with orbital metastases, likely due to the advanced stage of the malignancy at which metastases present, and treatment is typically palliative.(2)

Thyroid cancer treatment options include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, thyroid hormone therapy, or targeted therapy. (10) Surgery is the primary treatment option used for differentiated thyroid cancers. Thyroidectomy is recommended for follicular thyroid carcinoma that is invasive or with vascular infiltration or for papillary thyroid carcinomas > 1 cm. (11) Lymph node dissection is done if lymph nodes can be detected pre-operatively or intraoperatively. Radioiodine therapy (RIT) may also be done in high-risk patients to prevent recurrence. RIT may also be applied to certain metastases including bone and brain. (11) Lifelong thyroid hormone replacement is required after thyroidectomy.

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma has a poorer prognosis, and chemotherapy and certain targeted therapies like tyrosine kinase inhibitors or protein kinase inhibitors have been shown to prolong survival, although resistance frequently develops. (10,11)

Toraih et al. evaluated mortality of papillary thyroid carcinoma and found that patients with metastasis at initial presentation displayed an increased overall mortality rate (55.5%) compared to non-metastatic papillary thyroid cancer patients at initial presentation (4.3%). (12) Additionally, patients with multiple organ metastases at the time of diagnosis were associated with higher net thyroid-specific mortality (50.4%) versus patients with single organ metastasis (36.7%). The same study found that the one- and five-year overall survival rates for patients with single organ distant metastasis were 50% and 28%, respectively. These overall survival rates were markedly decreased in patients with multiple organ distant metastases (28% and 11%). Lastly, this study identified higher overall mortality rates in thyroid cancer cohorts presenting with brain (72.6%) and liver (68%) metastases compared to other regions of the body. (12) Our patient had cavernous sinus involvement at presentation, which portended a poor prognosis.

Management of thyroid orbital metastases depends largely on the stage of the diseases. Multidisciplinary approach between ophthalmologists, oncologists, neurosurgeons, and otolaryngologists is often required. Surgical debulking as needed, chemotherapy, radiation, and radioactive iodine are interventions that may be appropriate depending on each patient’s unique clinical picture. (13) Treatment goals may be curative or supportive, and a discussion of these goals should occur prior to the initiation of the treatment plan.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OR ETIOLOGY

|

DIAGNOSIS

|

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

|

Chun LY, Davis K, El-Geneidy M, Robinson RA, McKenzie D, Syed NA, Pham CM. Metastatic Thyroid Carcinoma. EyeRounds.org. January 23, 2025. Available from https://EyeRounds.org/cases/361-metastatic-thyroid-carcinoma.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.