Chief Complaint: 62-year-old female with blurry vision, redness and itching of the eyes.

History of Present Illness: The patient presented for a routine exam, stating that she had been bothered by what she claimed was a chronic "eye infection" intermittently for four years. Her flare-ups cause mattering of the eyelids, redness of the eyes, blurry vision and itching. She was seen initially by an outside physician and was diagnosed with an "eye infection" (the patient does not remember precisely what kind) and was given Neomycin/Polymixin/Hydrocortisone drops to use when she had symptoms. She reports that her symptoms abate somewhat when she uses these drops, but they always recur after she discontinues them.

Past Ocular History: The patient is pseudophakic in both eyes (OU) and she had a YAG laser capsulotomy, right eye (OD). She has lattice degeneration OD.

Medical History: She has hypertension and a history of stroke.

Medications: Hydrobromide, Benazepril, Diltiazem, Atenolol, Simvastatin, Aspirin, Potassium supplement.

Allergies: Sulfa drugs - not specified.

Family History: Mother has a history of retinal detachment, hypertension, and a stroke.

Social History: She smokes, but does not drink alcohol and works as a security guard.

Review of Systems: She reports a long-standing history of facial flushing. She is otherwise feeling well.

|

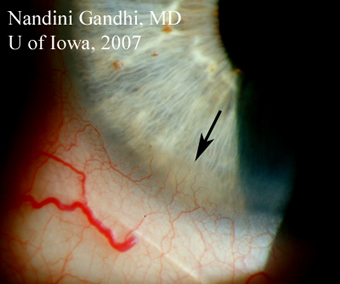

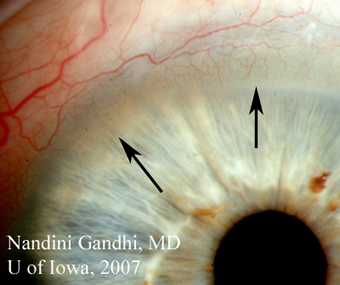

| 2A: Hyperemia and injection of the bulbar conjunctiva is evident. A small pannus is also seen in the inferior cornea (arrow). | 2B: Small pannus extending onto the superior corneal surface (arrows) can be seen in this view of the left eye. |

|

|

Course: The patient’s symptoms and anterior segment findings are fairly non-specific. However, her facial flushing, consistent with acne rosacea, strongly suggest that her ocular findings may be a part of the same process; namely, that she has blepharitis secondary to ocular rosacea. The patient was advised about proper lid hygiene including careful lid scrubs and twice daily warm compresses to the eyelids. She was also prescribed oral (PO) Doxycycline 100mg, twice daily (BID).

She returned to the clinic five weeks later, stating that although she "was not 100% better" her eyes were feeling much improved. On exam, her conjunctival hyperemia and lid margin erythema had completely resolved. Additionally, the debris and inflammation along the base of the lashes and orifices of the Meibomian glands was no longer present (see Figure 3). She was advised to continue her lid hygiene regimen and to reduce her Doxycycline to 100mg PO daily.

|

Epidemiology: Geoffrey Chaucer is credited with the one of the first descriptions of acne rosacea in The Canterbury Tales in 1387 (Donaldson, 2007). Today, acne rosacea affects approximately 14 million people in the United States and is characterized by flushing, erythema, telangiectasias and papules on areas of the face and neck (Stone, Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004). Ocular rosacea, first described by Arlt in 1864, is reported to occur in as few as 3% and as many as 58% of patients with acne rosacea, depending upon the study and whether a formal ophthalmologic exam was done (Akpek, 1997). The peak prevalence of ocular rosacea is among patients between 51 and 60 years of age. While cutaneous rosacea is twice as common in women as in men, ocular rosacea affects men and women in equal numbers. Rosacea, both cutaneous and ocular, is more prevalent among light-skinned people of European descent.

Pathophysiology: The exact cause of acne rosacea is unknown. The current teaching is that rosacea is an inflammatory disorder with an unknown initial trigger. The clinical features of facial flushing and erythema are thought to be a result of vascular dilation and incompetence in the affected areas (Stone, Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2004).

Ocular rosacea is also thought to be caused by local inflammation. This is supported by the observation that patients with ocular rosacea have elevated concentrations of the inflammatory markers interleukin-1alpha and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in their tear films (Stone, Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2004). A proposed mechanism is that patients with ocular rosacea have ocular micoflora that cause a chronic inflammatory response which, in turn, causes the variety of clinical findings described below. Ultimately, however, the definitive cause for ocular rosacea is unknown.

Clinical features: The most common symptoms of ocular rosacea are nonspecific, and include burning, tearing, redness, and foreign body or "gritty" sensation in the eyes. These symptoms are often out of proportion to the eye findings.

In a retrospective study of 131 patients with ocular rosacea by Akpek, et al, the most common findings were lid margin telangiectasias (81%), Meibomian gland dysfunction (78%), and blepharitis (65%). (Akpek, 1997). These findings were later echoed in a retrospective study of 176 patients with rosacea by Ghanem, et al. (Ghanem, 2003).

Conjunctival involvement usually presents as hyperemia, predominantly of the bulbar conjunctiva. Recurrent chalazia are commonly seen as well. Citcatrizing conjunctivitis and conjunctival granulomas are rare, but can occur. Likewise, episcleritis and scleritis have been reported, but are less common than conjunctival involvement. (Akpek, 1997).

Corneal involvement is the most sight-threatening aspect of ocular rosacea. One of the most common corneal manifestations of ocular rosacea is superficial punctate keratitis in the inferior half of the cornea, which generally does not impact sight. Chronic inflammation can lead to peripheral corneal thinning, scarring, vascularization and pannus formation. Patients with very advanced corneal disease may require penetrating keratoplasty or lamellar keratoplasty; of the 131 patients in the study by Akpek, 6 needed penetrating keratoplasties because of the extensiveness of corneal scarring. Grafts in rosacea patients are often thought to be more prone to rejection because of the significant amount of corneal vascularization (Browning, 1986).

Diagnosis: Ocular rosacea is diagnosed clinically; there are no formal criteria that have to be satisfied in order for the diagnosis to be made. However, the constellation of non-specific symptoms can be attributed to rosacea with certainty only if the patient also has the dermatologic features of the disease. This may complicate the diagnosis in those patients in whom the ophthalmic findings precede the cutaneous findings. Therefore, it is important in suspected rosacea cases for the ophthalmologist to take a thorough ophthalmic and dermatologic history, to recognize the features of cutaneous rosacea and to refer to dermatology in equivocal cases.

Treatment: One of the mainstays of therapy for ocular rosacea is appropriate eyelid hygiene and warm compresses to liquefy the sebum in blocked Meibomian glands. Medical therapy includes antibiotic therapy, most commonly tetracycline. The exact mechanism by which tetracycline treats rosacea is unknown; it is thought that tetracycline either decreases the amount of bacterial microflora, inhibits bacterial lipase (that produces toxic free fatty acids), or inhibits the matrix metalloproteinases (Stone, Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2004).

The evidence supporting tetracycline use for ocular rosacea is primarily based on non-placebo controlled studies. A masked, placebo-controlled study by Bartholomew, et al of oxycycline (a tetracycline derivative not available in the US), for the treatment of rosacea showed an improvement in symptoms in 65% of 35 patients. 28% of patients in the placebo group also experienced an improvement in symptoms (Bartholomew, 1982). This demonstrates a modest treatment benefit, and a significant placebo benefit. Placebo-controlled studies of tetracycline in the treatment of ocular rosacea would help inform the treatment choices that clinicians make.

Other antibiotic therapies include erythromycin, clindamcin, metronidozole, and ampicillin, but none of these have been studied in a prospective fashion. To treat the inflammation, topical steroids can be used have been reported to be effective in the prevention of recurrent corneal erosions. However, the risks of ocular hypertension and cataract formation make long-term topical steroid therapy a less favorable long-term solution. It is thought that other topical anti-inflammatories like Restasis (cyclosporine) may benefit patients with ocular rosacea, but these have not been formally studied yet (Stone, Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2004).

Rosacea in children: Although rosacea is thought to be a disease of the fourth and fifth decade, children can also be affected. Because pre-pubertal children often do not have the cutaneous manifestations of rosacea. their non-specific eye findings are often attributed to infectious or allergic keratoconjunctivitis. Although many children may not have the cutaneous clues, the diagnosis of rosacea should be considered for children with non-specific symptoms who do not respond to therapy (Nazir, 2004). In children, tetracycline and doxycycline should be used with caution because of the known side effect of depressing bone growth. In their review of 20 children with ocular rosacea, Donaldson et al describe a stepwise approach to treatment in children that involves starting with lid hygiene and topical erythromycin ointment. They recommend systemic therapy for patients whose symptoms are refractory to local therapy; they recommend oral erythromycin for children under the age of 7 and oral doxycycline for older children. (Donaldson, 2007).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

(The differential diagnosis of "red eye" or conjunctivitis is lengthy and will not be reproduced at length here. Differential diagnosis for follicular conjunctivitis or for an picture of vernal conjunctivitis are similar to the differntial for ocular rosacea and can be found in the links below)

Gandhi N, Oetting TA: Ocular Rosacea: 62-year-old female with blurry vision and red, itchy eyes. EyeRounds.org. November 18, 2007; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/77-Ocular-Rosacea-Blurry-Red-Itchy.htm

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.