Chief Complaint: Blurred central vision in the left eye.

History of Present Illness: A 30-year-old white male noticed central visual distortion and loss of vision in the left eye (OS) over the past few weeks. His local optometrist referred him to the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences for further evaluation.

Past Ocular History: None.

Medical History: The patient reported no prior systemic diseases or illnesses.

Medications: None.

Family History: No familial eye diseases and otherwise noncontributory.

Social History: Married, lives with his wife. He works as a computer programmer. The patient has lived in the Mississippi River Valley for his entire life.

Ocular Exam:

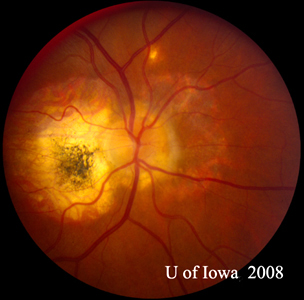

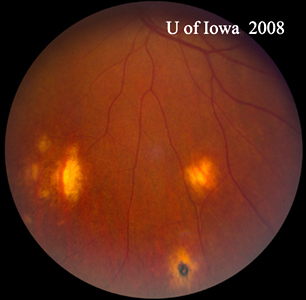

| A: 30-degree fundus photo, OD. Note the peripapillary atrophic changes. | B: 30-degree fundus photo, OS. Similary peripapillary atrophic and pigment changes are evident. Note the chorioretinal "histospot" within the macula and the absence of any vitreous inflammation. |

|

|

|

A: Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) scans of both eyes shows an increase in central macular thickness (CMT) OS (295µm) compared to OD (205µm). A). |

B: Note the presence of subretinal fluid and distortion of the foveal depression, OS. |

|

|

Course: This patient has a history and clinical appearance strongly suggestive of the presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS). While his thick, yellow macular lesion is not perfectly classic (see Figure 5 and Discussion below), all indications suggest that a choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) has developed in this left macula at the site of a chorioretinal scar. We discussed at length with the patients the options for treatment, including established clinical studies for macular laser or photodynamic therapy (PDT) to the lesion. Additionally, the patient was informed about early results in the literature and personal experience suggesting good results with the off-label use of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin). The patient chose intravitreal injection, which was accomplished without complication. He was seen again at four weeks following the injection by which time his vision had improved to 20/20 and the retinal lesion was dry both clinically and by OCT (Figure 4).

|

Discussion: Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (POHS) is a clinical diagnosis made based on a constellation of ocular findings that were originally described in 1960. The syndrome is an inflammatory disorder that has been postulated to result from systemic infection with the dimorphic fungi Histoplasma capsulatum. There have however, been no confirmatory studies which directly implicate this fungus in the pathogenesis of the disease. Rather, epidemiological data suggests that the prevalence of POHS is greatly increased in areas that are endemic to the Histoplasma organisms. Classically, people living in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys are known to have as high as a70% rate of positive skin test for exposure to H.capsulatum. Indeed, the vast majority of patients with POHS react positively to this skin test. However, only about 4.4% of patients with a positive skin test have evidence of POHS. Therefore, the relationship between H. capsulatum and POHS remains presumed. [1,2]

Of note, patients with POHS are often young and otherwise healthy and the retinal lesions can produce significant functional visual loss in this working age population.

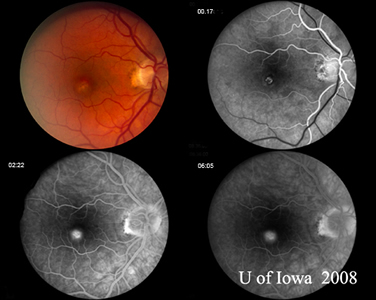

The diagnosis of POHS is made based upon the identification of classic fundus findings. These are the presence of peripapillary atrophy or pigmentation, the presence of characteristic "punched-out" chorioretinal atrophic lesions, and the absence of overlying vitreous involvement. The peripapillary changes are thought to represent a regressed choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM), and the "punched-out" lesions are thought to represent areas of hematogenous seeding of H. capsulatum to the retina. It should be noted that many of the peripheral "punched-out" chorioretinal scars may well be associated with small CNVMs as well that are not brought to attention clinically and regress spontaneously. Classic examples of these lesions can be seen in Figure 5. Often times, as in the case presented here, POHS will present to the attention of the ophthalmologist with a symptomatic CNVM involving the macula or fovea. In this case, the macular lesion was somewhat unusual with a thick yellow substance to it, whereas the CNVM in POHS is often a gray-green lacy net arising from a chorioretinal scar (see Figure 6) that is defined early in the angiogram and leaks late.

| A: POHS in a patient with significant peripapillary atrophy and pigment change, demonstrating the appearance of a regressed peripapillary CNVM that has been postulated as the source of these lesions. | B: Peripheral chorioretinal scars in a patient with POHS. |

|

|

| A: Gray-green macular CNVM in a patient with POHS | B: Fluorescein angiogram of the patient in Figure 6A demonstrates classic leakage pattern associated with CNVM in patient with POHS. |

|

|

The pathogenesis of the CNVM is unknown; however, several authors have suggested that following hematogenous spread of the organisms to the retina, areas of focal inflammation occur, leading to a disruption in Bruch's membrane, and thus predisposing to CNVM formation. POHS has also been postulated to result from autoimmune trigger, which is spurned by the presence of the infectious organism. In any case, patients are usually either identified while asymptomatic (minority) or come to the attention of an ophthalmologist with complaints of decreased vision.

The treatment of POHS has evolved over the past several years, and while there is no direct therapy to target the organism, several modalities have been identified as beneficial in the treatment of the accompanying CNVM. Historically, laser photocoagulation resulted in inhibition of well-defined, classic extrafoveal, juxtafoveal, and peripapillary lesions in POHS could be achieved. However, the resultant central scotoma was sometimes unacceptable in lieu of newer therapeutic options. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with verteporfin was approved by the FDA for the treatment of CNVM related to POHS in late 2001 and was shown to be safe and effective for treating the disease. Once anti-VEGF agents were proven to be effective in the treatment of CNVM related to AMD, case reports were published in the mid 2000s showing their success in the treatment of neovascular membranes in patients with POHS. After the publication of numerous case reports and retrospective reviews showing the efficacy of treatment with anti-VEGF agents, they have become the standard of care utilizing the same principals as those for treating AMD related CNVM.[3-8]

Diagnosis: Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (POHS) with CNVM

EPIDEMIOLOGY

|

SIGNS

|

SYMPTOMS

|

TREATMENT

|

McConnell LK. Revision of [Cohen AW, Graff JM. Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis (POHS): 30-year-old male with blurred central vision. EyeRounds.org. May 8, 2017.]; EyeRounds.org. July 5, 2017; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/83-Presumed-Ocular-Histoplasmosis-POHS.htm.

Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.