Section 9-A: Introduction to acute angle closure glaucoma

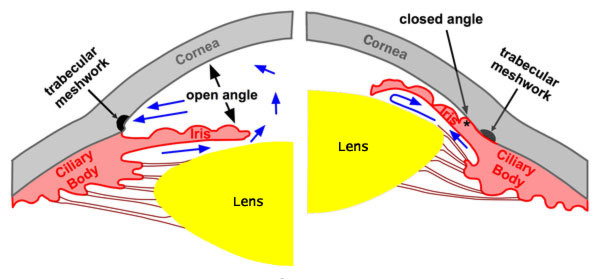

Acute angle closure glaucoma is a serious eye condition in which the drainage angle becomes obstructed such that aqueous humor cannot make its way out of the eye. The iris and cornea become pressed together and consequently, aqueous fluid cannot get to the trabecular meshwork and make its way out of the eye (figure 9-1). The result is a rapid elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP) that causes a constellation of symptoms including decreased vision, seeing halos around bright objects, pain, and nausea (Table 9-1). The intraocular pressure may become dangerously high and prompt treatment is necessary to prevent irreversible vision loss.

The most common form of angle closure glaucoma involves blockage of the pupil by the lens (pupillary block) and occurs in eyes that have narrow drainage angles. Pupillary block occurs when the lens comes in close contact with the iris around the pupil and prevents aqueous fluid from moving through the pupil. Aqueous fluid collects behind the iris and causes it to bow forward and close the drainage angle. The iris bows forward in the periphery and blocks aqueous fluid from reaching the trabecular meshwork and exiting the eye. This abnormal configuration of the iris prevents normal flow of aqueous fluid through the pupil to the trabecular meshwork and causes an acute rise in intraocular pressure (Figure 9-1).

Figure 9-1. Acute angle closure glaucoma. Left: In an eye with a normal configuration of the anterior segment, the angle between the iris and cornea is wide open (approximately 40˚). Aqueous fluid has free access to the trabecular meshwork and exits the eye unimpeded. Right: In an eye with acute angle closure, the angle between the iris and the cornea is obstructed and closed. Aqueous fluid is trapped within the eye and causes the intraocular pressure to rise rapidly.

| Symptoms of acute angle closure glaucoma. |

|---|

| Decreased vision |

| Seeing “halos” |

| Pain |

| Nausea |

Section 9-B: Risk Factors for acute angle closure glaucoma

There is variation in the size of the human eye. Some individuals have eyes that are slightly smaller than the average. In such smaller eyes, there is relatively less space for the normal structures of the eye (ciliary body, lens, and iris) and consequently, these eyes have “crowded” drainage angle. The result is narrower drainage angles with less space between the lens and iris and higher risk for pupillary block and acute closure of the drainage angle (Figure 9-1). The drainage angles of smaller eyes are therefore at higher risk of becoming critically narrow or closed. Consequently, acute angle closure glaucoma occurs most commonly in people with traits that are associated with smaller eyes (Table 9-2).

| Risk factors for acute angle closure glaucoma. |

|---|

| Female gender |

| Older age |

| Large natural lens (cataract) |

| Far-sightedness (Hyperopia) |

| Short axial length of the eye |

| Dim illumination |

| Certain medications that cause the pupil to dilate in susceptible eye |

Acute angle closure glaucoma is more common in females because females have eyes that are generally smaller than those of males. Similarly, angle closure glaucoma occurs more frequently with increased age, because as the lens of the eye grows larger with age, the anterior segment of the eye becomes more crowded and the drainage angle becomes narrower. People with eyes that are physically smaller are generally far-sighted (hyperopic) and require more corrective power for seeing nearby objects than faraway objects. Such far-sighted individuals are at greater risk for acute angle closure glaucoma, because the drainage angle in their smaller eyes is more crowded than in individuals with normal sized eyes.

The risk for pupillary block and angle closure is increased when the pupil is dilated by dim illumination or by medication. As the pupil gets bigger, the bulk of the iris moves towards the angle causing it to become more crowded and narrower. Dilation of the pupils can cause narrow angles in susceptible individuals to become abruptly closed.

When critically narrow angles are observed by an eye doctor, preventative laser surgery (laser peripheral iridotomy) is recommended to reduce the risk of angle closure glaucoma occurring (see Section 9-D).

Section 9-C: Diagnosis of acute angle closure glaucoma

Acute angle closure glaucoma can be diagnosed with an examination by an eye doctor. Some of the common signs of acute angle closure may be recognized by examination of the eye (Table 9-3).

| These findings of acute angle closure glaucoma are seen in an examination by an eye doctor. |

|---|

| Cloudy cornea |

| Red eyes |

| Forward bowing iris (narrow drainage angle) |

| Mid-dilation of the pupil |

| High intraocular pressure (several times higher than normal pressure) |

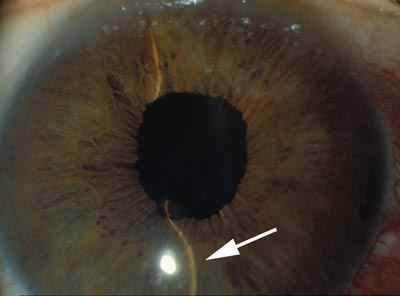

Pupillary block and obstruction of the drainage angle causes the iris to bow forward, which can be recognized with a slit lamp exam by an eye doctor (Figure 9-2). This abnormal configuration of the iris and cornea blocks outflow of fluid from the eye and causes the IOP to become rapidly elevated.

Figure 9-2. Abnormal forward bowing Iris characteristic of acute angle closure glaucoma. A key feature of acute angle closure glaucoma is the abnormal forward position of the iris. Forward bowing of the iris may be observed by an eye doctor with a slit lamp examination. When a straight beam of light is projected on an eye with acute angle closure glaucoma, the beam (indicated by an arrow) appears curved due to the forward bowing of the iris.

Figure 9-3. Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma: External Appearance. Blockage of the drainage angle causes IOP to rise. High pressure results in a constellation of signs seen in acute angle closure glaucoma including redness of conjunctiva (red arrow), haziness of the cornea, and a mid-dilated pupil (white arrow).

When the IOP becomes very high, the “whites” of the eyes become red. High IOP also causes the normally clear cornea to become hazy which results in significant decreases in vision. Changes in the cornea may also cause patients to see halos around bright objects. Finally, high IOP may cause the pupil to become partially dilated and poorly responsive to light (Figure 9-3).

Rapid elevation of IOP is a key feature of acute angle closure glaucoma. The pressure may rise as high as several times the normal IOP and can cause permanent and significant vision loss. Consequently, it is crucial to treat acute angle closure glaucoma promptly.

Section 9-D: Treatment of acute angle closure glaucoma

Intraocular pressure may be critically high in acute angle closure glaucoma. The goals of treatment are to lower the pressure as soon as possible and to prevent further attacks. Initially, acute angle closure glaucoma is treated with a range of medicines that may be given as eye-drops or pills. In rare cases intravenous medications may also be used. However, the definitive treatment for most cases of angle closure glaucoma is laser peripheral iridotomy.

In most cases of angle closure glaucoma, medications are used first to lower the eye pressure to a point at which the laser peripheral iridotomy (see Chapter 8-A-2) can safely be performed. While medications may temporarily treat an episode of acute angle closure, laser peripheral iridotomy is necessary to definitively treat and prevent future attacks. The treatments for acute angle closure glaucoma are discussed in more detail below:

Topical medications. Most of the same eye-drops that are used for chronic forms of glaucoma (chapter 7) are also used to treat acute angle closure glaucoma. The combined use of several medications are generally required to sufficiently lower intraocular pressure.

Three classes of medications reduce the production of aqueous fluid (beta blockers, alpha adrenergic agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) and thereby lower pressure in the eye. These aqueous suppressant medications are useful in lowering the pressure in acute angle closure glaucoma. Rapid application of a series of beta blockers, alpha adrenergic agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors eye drops will often lower intraocular pressure sufficiently to to allow definitive treatment with a laser (see below).

Once the eye pressure has been lowered with other medications, cholinergic eye drops may be used to pull the iris centrally in preparation for a laser treatment. The cholinergic eye-drops stretch the iris and make it easier for the laser to produce a hole in the iris (see below).

Oral medications. When topical eye-drops fail to lower intraocular pressure to safe levels, oral medications may be necessary in treating acute angle closure glaucoma. Two forms of oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (acetazolamide and methazolamide) can be used to treat acute angle closure glaucoma by reducing the production of aqueous fluid. Occasionally, a hyperosmotic drug (glycerol or isosorbide) may be used. The latter medications help to draw fluid out of the eye and into the bloodstream, thereby lowering the IOP.

Intravenous medications. Intravenous medications may rarely be necessary when topical and oral medications fail to adequately lower the intraocular pressure or when a patient is too sick to take oral medications. Intravenous hyperosmotics (urea or mannitol) may be used in these situations.

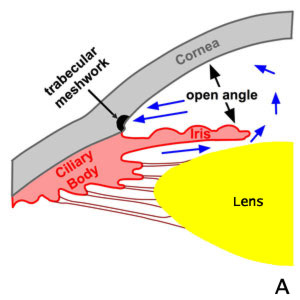

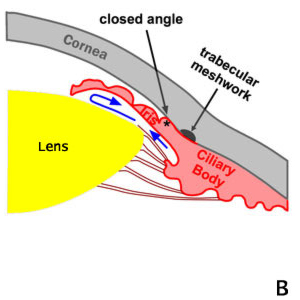

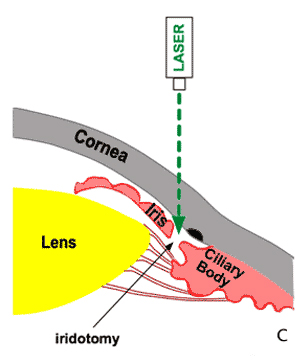

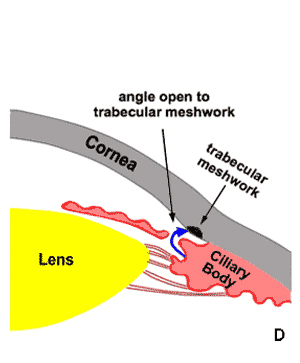

Laser treatment (Laser Peripheral Iridotomy). A laser peripheral iridotomy to break the pupillary block and acute closure of the drainage angle should be performed as soon as possible after using medications. The goal of a laser peripheral iridotomy is to produce a hole in the iris to relieve the papillary block and allow aqueous fluid to make its way to the trabecular meshwork, thereby lowering the IOP (Figure 9-4).

A. Normal

B. Pupillary Block. Angle Closure

C. Laser Treatment of Angle-closure (iridotomy)

D. Open angle following laser iridotomy

Figure 9-4. Laser Peripheral Iridotomy. The definitive treatment for acute angle closure glaucoma is laser peripheral iridotomy. A. Normal flow of aqueous humr in an eye with an open drainage angle. B. In acute angle closure glaucoma aqueous humor cannot pass through the pupil (pupillary block). Fluid collects behind the iris causing it to bow forward and close the drainage angle. The obstruction of aqueous humor drainage causes a rapid rise in intraocular pressure. C. The treatment for acute angle closure glaucoma using the laser to produce a hole in the iris (laser iridotomy). D. Aqueous humor can bypass the pupil and make its way to the trabecular meshwork and out of the eye. Bypass of the pupillary block reduces bowing of the iris and opens the drainage angle.

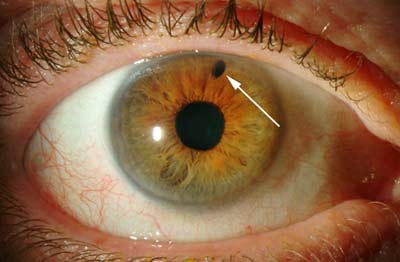

The small hole in the iris created by laser peripheral iridotomy is not easily recognized by the naked eye but is easily seen by an ophthalmologist during an eye exam (Figure 9-5).

Figure 9-5. Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI). The laser treatment for acute angle closure glaucoma creates a small hole in the iris (arrow) that is visible with an eye examination.

Section 9-E: Prevention

Before any attacks occur (prevention for both eyes). Critically narrow drainage angles may be recognized prior to an attack of acute angle closure. Such drainage angles may be identified by an eye doctor by gonioscopy (Chapter 6-C). When detected, critically narrow drainage angles need treatment with a laser peripheral iridotomy (see above) to prevent attacks of acute angle closure glaucoma. In most cases laser peripheral iridotomy is performed in one eye at a time, within a few weeks of each other.

After an attack (prevention in the other eye). When a patient has an attack of acute angle closure glaucoma in one eye, it is treated emergently. In many cases, the fellow eye also has a critically narrow drainage angle and is at high risk for acute angle closure as well. A laser peripheral iridotomy should be performed to prevent acute angle closure in the fellow eye as soon as the eye with acute angle closure becomes stable after treatment.

Chapter 9. References

Allingham RR, et al., editors. Shields’ Textbook of Glaucoma, ed. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. pp. 217-234.

Alward WLM. Glaucoma. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000. pp. 141-154.

Simmons RB, Montenegro MH, Simmons RJ. “Primary angle-closure glaucoma”. In Tasman W ed. Duane’s Clinical Ophthalmology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. Chapter 53.